Exhibition | May 3rd – June 16th

Opening reception | May 3rd 6 – 8 PM

Fool’s Gold, the title of the exhibition, is also the common name for pyrite, etymologically meaning “fire stone” in ancient Greek. This name dates back to the days of the gold rush, and the fact that those prospectors confused this relatively valueless stone with the gold-bearing ore which they desperately hoped to unearth. All that glisters is not gold, but, fateful irony, pyrite does contain minute traces of it. So reality is misleading, at least twice over. The use of minerals as a raw material, as well as every manner of sham, is a recurrent device in Evariste Richer’s work.

Whence, here, the use of lures, as in Parrot and Over & Under. The object on view and the object photographed are in fact inspired by a variety of angling lures (“flies”) which the artist has designed and had made for the show. In Over & Under, the mock-gold emergency blanket (it is in effect a completely synthetic product, Mylar), covers with a protective pledge the trap laid for anyone feeling like taking hold of it.

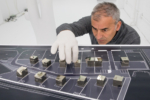

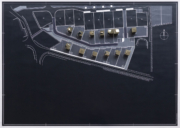

Gold prospectors were indeed lured by pyrite, but they also really set up shop in sites where it was mined, as if that carnivorous rock had attracted and snared them, triggering the creation of the American landscape of “sprawling cities”. In Pyrite City, cubes of pyrite are placed on a subdivision plan, like hotels on a Monopoly board. The stones are laid out in batches, like the list of atoms in a table of elements. The dream of gold is turned into a real-estate project.

Political Moon

Lune politique – 2017 – Inkjet print on Baryta Hahnemühle – 132 x 132 cm unframed – 52 x 52 inches – Edition 2/3

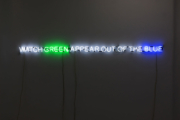

Watch green appear out of the blue

2014 – neon, transformers – 224 x 8 cm – 88.2 x 3.2 inches – Edition 2/3 – ©Jenny Gorman

Le Poids du monde dédoublé

The weight of the duplicate world – 2014 – Precision scale Pesola, CYMK Color chart Kodak – 6 x 46 x 1.5 cm – 2.4 x 18.1 x 0.5 inches – Edition 2/3

Pyrite City

2019 – Subdivision project plan 46.81 x 33.11 inches, 13 pyrites, Eiermann architect table – Unique – ©Jenny Gorman

Your Home

2017 – Inkjet print on Baryta Hahnemühle – 84.1 x 59.4 cm unframed – 33.1 x 23.4 inches – Edition 1/3

Watching the green grow

2019 – Inkjet print on Baryta Hahnemühle – 84.1 x 59.4 cm unframed 33.1 x 23.4 inches – Edition 1/3

Pinching the blue

2019 – Inkjet print on Baryta Hahnemühle – 84.1 x 59.4 cm unframed – 33.1 x 23.4 inches – Edition 1/3

The lure is used to fool, but, more exactly, to catch the attention of whatever it is aimed at. Historically, this is indeed how art has been described by suspicious philosophers and theologians. Art grabs and monopolizes the eye, but it diverts the mind from intelligible essences. In this show, the lure works like a symbolic equivalent of art.

With art, human beings make lures designed for themselves. Belief in the image and the suspension of disbelief are essential mainsprings which make it possible for the onlooker to fool himself. The work on view is also an active reflection about this mechanism which skims the surface of things, and discovers their bottom, or double bottom.

A prospector in another field—poetry—had these words inscribed as an epitaph on his grave: “I am looking for the gold of time”. Evariste Richer follows a similar vein, seeking poetry in mineral formations—time’s condensation in its geological form. He replaces the processes of classical artistic deformations, such as anamorphosis, with the phenomena of pseudo-morphosis (i.e. an object’s altered nature like, for example, the phenomenon of “petrified” trees–turned into stone.)

This poetic projection is explicit, though in a hijacked form, in the piece titled Lune politique / Political Moon, a photo of a “pyrite sun”. The look of it conjures up a lunar image, another fantasized “frontier” and political goal of the 1960s. The title is an allusion to the “poetic world” of Marcel Broodthaers, and more specifically to two pieces (Soleil politique/Political Sun, 1972, and Carte du Monde Poétique/Map of the Poetic World, 1969). What is meant by the “political world”, in geography, is the mapping of the borders of States. And if politics fights for their permanence, poetics is there to remind us of the changing and egregiously conceptual nature of these boundaries.

Watch Green Appear Out of the Blue spells out its own title in glowing letters. Referring to the advertising slogan of the NYC Lottery, the piece thus to all appearances borrows the literal form of enunciation of Joseph Kosuth’s neon works. But unlike this latter, and his idea about a “tautological” definition of art, one thing here suggests another. The colour coincides with the word, but the sentence conjures up a transformation.

The blue and green referred to have actually come from nowhere, with the neon somehow linking the two other pieces in the show, Pinching the Blue and Watching Green Grow. The first shows a blue stone (smithsonite) held by the artist’s hand, “inlaid” on a green background, while the second shows the same hand holding green sellenite crystals, this time on a blue ground. These colours used for filming subjects on video are a “nowhere”, a sort of abstract non-site, which helps to separate the filmed subject from one background and replace it with another. The two images suggest a fossilized landscape—a fragment of pinched sky, a crystallized tuft of grass, while the contact with the hand suggests that the person grasping these rocks is experiencing a Braille landscape.

A last lure seems to encompass them all: Le Poids du monde dédoublé / The Weight of the Duplicated World consists of a precision scales with a CMJN Kodak colour chart hanging from it. A weighing instrument, and an image making it possible to check the exactness of a colour in its reproduction process. The two instruments seem to cancel their respective functions, the colour weighing nothing, and the scale being devoid of colours. Their respective neutralization refers us to the non-measurable, to something that measurement has no hold on, which is the poetic world.

Vincent Pécoil

Evariste Richer (b. 1969 Montpellier, France) lives and works in Paris.

By measuring, mapping, classifying, and archiving, man has invented plenty of methods and systems for reducing the world to his human scale. Although the history of art and of the sciences seems to reflect the procession of human conquests with a great sense of partnership, Evariste Richer’s work diverts our eye fixed on the rear-view mirrors of our norms to reveal the blind spot, inaccessible to our field of vision. A broad corpus of his works retraces the Wild race of the human species to impose its systems of measurement on the world and bring the universe back to it.

The dual heartbeat of breathing in and breathing out, of assimilation and expulsion of the human eye is there at the heart of Evariste Richer’s oeuvre. A fertile overlap between a Renaissance cabinet of curiosities and the mental mechanics of Conceptual Art, the artist’s work somehow grasps the current debates and theories deriving from the Anthropocene, meaning the testing of man as the geocentric force of the universe.

Excerpts from “To the moon and back” text by Florence Ostende in the 2014 Marcel Duchamp Prize catalogue

Vincent Pécoil is an art critic, translator, and exhibition organizer. In particular, he has worked with the magazines Art Monthly, Art & Text, Les Cahiers du MNAM, Kunst-Bulletin, Parkett, Tate Etc, and contributed to many exhibition catalogues.